„It wants to be a place of lifelong learning. Conscious of its history, the University of Cologne realizes the freedom of science and is aware of its historical responsibility. To realize this mission, it is committed to a culture of understanding and cooperation. (…) The University of Cologne develops its contribution to a sustainable, peaceful and democratic world by fulfilling its (…) tasks independently of non-scientific requirements.“

Cologne university constitution, resolved on June 2015

Unlike companies, public authorities and many other organizations, universities are in principle self-organized, i.e. the people who work at universities decide themselves on the goals and organization of their work. However, this does not mean that universities are automatically democratic, nor that they are not pressed into service for a wide variety of interests. On the contrary: universities produce truth; they can enlighten with explosive force about social grievances or provide legitimation for the status quo. And it has always been disputed whose problems they solve and in whose interest.

Universities – historically contested

„On the university council – that’s mad – are Bayer and Deutsche Bank.“

The „Higher Education Freedom Act“ of 2007 installed „university councils“ at universities, which were dominated by large companies and employers‘ associations. They were given far-reaching opportunities to change decisions made by the universities and to intervene in the appointment of rectorates, which were also strengthened compared to all other university bodies. In fact, the university councils hardly made use their rights; instead, the universities anticipated the wishes of the university councils.

During the „education strikes“ in 2009 and 2011, students protested against the „entrepreneurial“ orientation of universities and schools, which at universities was essentially based on the „pillars“ of tuition fees, the „Higher Education Freedom Act,“ the „Excellence Initiative,“ and the orientation of the then newly introduced Bachelor’s-Master’s programs.

Decisive parts of the „entrepreneurial“ orientation have since been overcome: Tuition fees have been abolished again, significant concessions had to be made in the new rounds of the Excellence Initiative, the courses of study are becoming more student friendly step by step as a result of ongoing reforms in most subjects, and the „University Future Act“ of 2014 has strengthened and partially democratized the university bodies.

Thus, during the Enlightenment, universities contributed significantly to the rationalization and demystification of the worldview and thus to the disempowerment of the churches.

They fueled the First World War through weapons development and scientifically legitimized war propaganda. Under National Socialism, scientists were persecuted at numerous universities even before the transfer of power, and students eagerly participated in book burnings; every year, therefore, readings from the books burned at the time are held on campus in order to jointly appropriate the ideas that were so dangerous to the Nazis that they tried to eliminate them from the world.

As a consequence of this, the student movement in particular fought for a social opening of universities in the 1960s and 1970s. On the one hand, the goal was to enable everyone to study at universities. On the other hand, all social groups were to be represented at the universities so that they would also act in the interests of all and not just an elite. This was accompanied by a cultural change from the cult of the brilliant professor to a political discussion about the orientation and functioning of universities, which was also reflected in the fact that non-professors were given more say in university committees. At the same time, universities contributed significantly to the liberalization of German society in the 1970s and to the peace movement of the 1980s.

The 1990s and 2000s, the times of the so-called entrepreneurial university, were characterized by strong pressure on universities, built up by competitive mechanisms and systematic underfunding, to submit themselves to the demands of employers. A cooperation agreement concluded in 2008 between the Cologne University Hospital and Bayer, for example, attracted a great deal of public attention. It was known that the university received money from Bayer and it was suspected that in return Bayer had secured a say in the selection of research questions and the publication of results. However, the contract, which has expired in the meanwhile and was also not extended due to the protest against it, is secret to this day in order „not to endanger the business interests“ of Bayer.

Another prominent Cologne example is a report by the Institute of Energy Economics of the Wiso Faculty, which at the time was largely financed by the major German energy companies (today largely from state funds) and played a major role in the debate about the nuclear power plant lifetime extension in 2009/2010 (shortly before the reactor accident in Fukushima). At the time, the Spiegel magazine headlined that the University of Cologne had been bought, which the university rejected by pointing out that the study was scientifically correct. In fact, there is rarely scandalous falsification of research results. What is more controversial is which premises studies are based on, whether the results are published, and above all which research questions are pursued and which are left out.

Backward roll?

In 2014, universities in NRW were given the legal mandate to develop „their contribution to a sustainable, peaceful and democratic world“ (civil clause). The rights of non-professors to have a say were strengthened, committees for the further development of study programs (study advisory boards) were introduced in which students have a veto right, the working conditions of university employees were improved and compulsory attendance at courses was abolished.

Then in 2017, a conservative-neoliberal state government stepped in with a plan to restrict this again. Because the statewide civil clause in particular is, according to the federal government’s assessment, one of the 10 crucial obstacles to „the endeavor to strengthen the security-industrial complex.“ In the summer of 2019, then, the law was changed again against widespread protests, giving universities the „freedom“ to reverse some of the 2014 improvements.

Parallel to this, „Fortress Europe“ should also be secured at universities through AfD-compatible tuition fees of €3,000 per year for non-EU foreigners.

Where to put all the money?

In November 2019, under the heading „Courage to Reason,“ the responsible minister announced the final burial of the fee plans and, at the same time, an increase of around 30% in the universities‘ basic funding („Future Contract“). – A breakthrough that probably no one had expected. The decisive factor was certainly that not only students protested against the fee plans, but the universities as a whole joined the protests on social grounds. The first and very remarkable public statement came from Cologne.

At present, it is still partly open what will happen with the new funds. In the meantime, however, it has become clear that the universities are neither pursuing the abolition of the civil clauses, which can still be found in the constitutions of the universities, nor the restriction of co-determination. On the contrary, the senate of our university, for example, has largely endorsed the demands of the plenary assembly convened by Students for Future in December 2019, and it is likely that the signature campaign „For a World Without Nuclear Weapons,“ which originated in our „Physics & Ethics“ seminar, will be discussed there this semester.

The show must go on

In the midst of the debate about what the university should do now with these new conditions, the Corona crisis burst, the biggest reorganization of the universities in the last 50 years, which took place completely without planning, public debate and in only a few weeks.

Lack of face-to-face meetings (universities are the only public sector that was quasi completely closed for 1.5 years without interruption), students who lost 40% of their part-time jobs, lecturers who worked 90 hours a week without leave to maintain a nevertheless unsatisfactory online operation as best as possible, and a rectorate that is primarily concerned with three major projects:

A pilot project was launched under the name „EUniwell“ to unite the degree programs of 7 European universities. Sounds ambitious, and it is. Open questions above all: What exactly is gained by this? How are travel costs to be paid if not everything is online – which no one seems to want to do after the last few semesters.

Unlike schools, for example, which are given their curricula by the state government, universities design their courses completely themselves. However, there is something like quality control at the very end. This used to be the responsibility of the state ministry, but in the mid-2000s it was outsourced to external accreditation agencies under the name of „program accreditation,“ which consist of a strange mixture of university members and lobbyists and are thus poorly legitimized, a lot of work and expensive. In the face of widespread criticism from various sides, the University of Cologne – like many other universities at present – is switching to „system accreditation“. The idea is that the final quality control will take place within the university itself and that study programs will no longer be reformed every 5 years in one big act, but will be continuously improved in small steps. In order for the university to receive approval for this, however, all possible structures must be changed in such a way that it is also systematically ensured that problems are noticed and dealt with, and that opportunities for improvement are not just taken at random. Above all, however, the university itself must define what actually constitutes the „quality of a study program.“

All of this also feeds into the third major university-wide project, a „strategic plan“ for the period up to 2030. Here, the main issue is also what money is spent on. And this is not just about the additional money from the „Future Contract“, but also about existing funds.

Crises & directional issues

With all the debates taking place right now, one thing is clear: Almost without exception, people in Cologne are now in favor of the university taking on social responsibility; this was unthinkable just 10 years ago. What this means in view of the recently proclaimed „turn of the times“ is something we must determine together and in debate. Among other things, the lecture series „Interdisciplinary Forum: Peace & Susceptibility“ was established, the student council participated in demonstrations, the Faculty of Arts and Humanities took a stand in favor of the treaty banning nuclear weapons in view of the current escalation of war, and the Faculty of Mathematics and Natural Sciences is preparing a statement right now.

However, it is always unclear in these discussions: Do you have to fit into the system in order to achieve something, or do you have to blow up the system? Do you have to be excellent before you have a say, or do you first have to abolish the focus on excellence so that everyone can have a say? And what does excellence actually mean? Does it mean polishing your reputation until you can choose the „world’s best“ students and staff, or does it mean offering students and staff excellent working conditions so that they don’t have to constantly prove themselves in competition? And do you actually have to work with the big corporations to save the climate, or do you have to expose their dirty tricks?

Structure of the University of Cologne

Irrespective of the situation in science policy, the self-governing bodies of the universities were and are of great importance, because it is here that the concrete work on the further development of the university takes place. The extent to which interested parties interfere depends above all on how much the committees allow themselves to be interfered with. A good example of this is that a few years ago, the Senate at the University of Siegen protested against the rector that the University Council wanted to appoint, with the result that parts of the University Council resigned and the candidate desired by the Senate became rector.

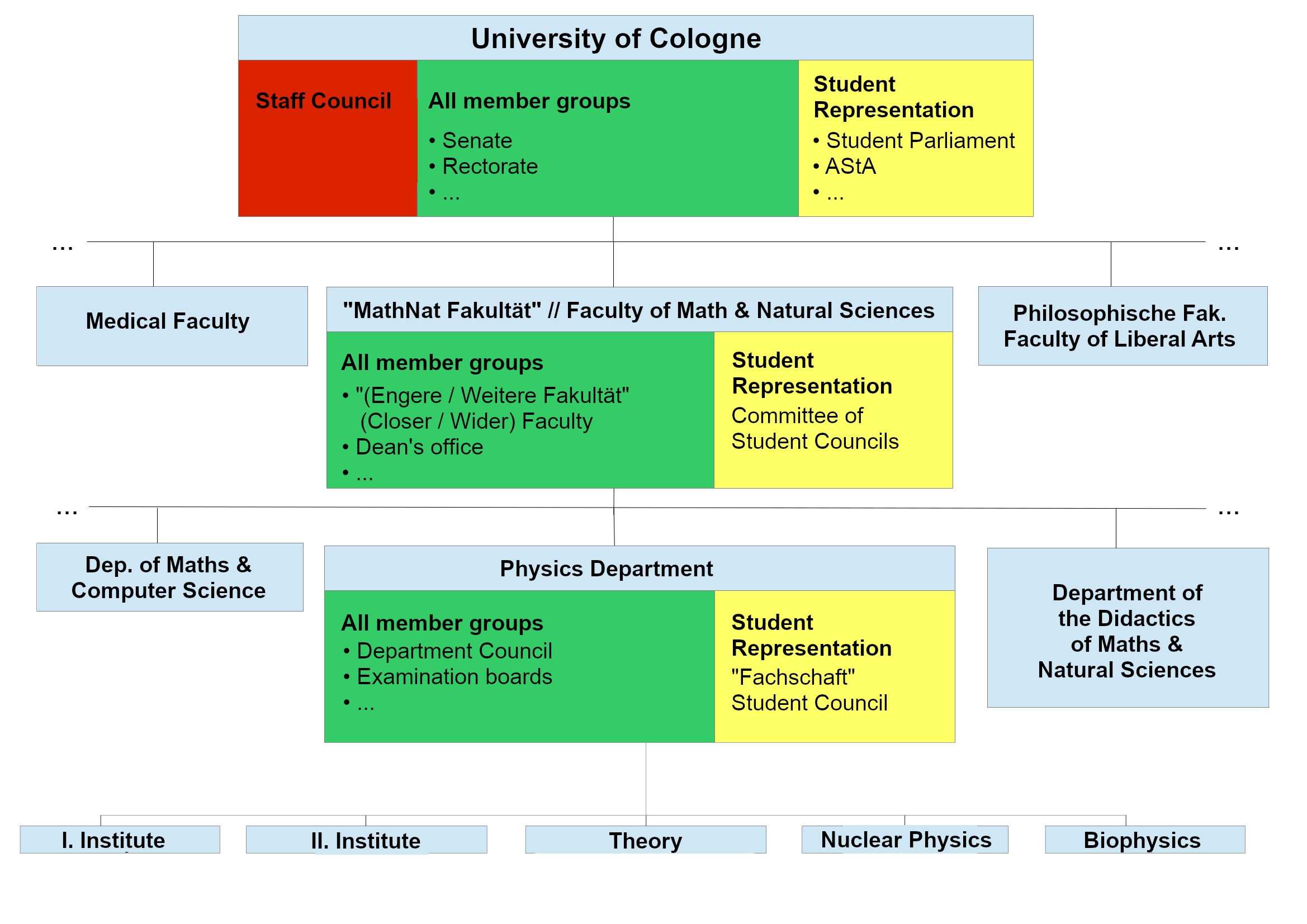

The structures of the University of Cologne have grown historically and have many idiosyncrasies. In general, however, the following applies: people who conduct research in the same field form an institute; the institutes that together offer (partial) courses of study form a department; departments that share certain cultural commonalities form a faculty. The faculties together form the entire university.

Committees

At each of these levels there is a central collegial body (green) in which all member groups (professors, students, academic staff, technical and administrative staff) are represented and jointly decide on their affairs (senate, faculty meeting, departmental committee). As a rule, there are also people who take care of the day-to-day business (rectorate, dean’s office, departmental chair) and numerous commissions that assist in certain matters. This is the basic structure. Deviating from this, there are numerous special regulations (both in the university regulations and in the Higher Education Act), in particular the rectorate and the deaneries have more power in many places.

In addition to the joint bodies explained above, students at all levels have their own bodies (yellow) in which they organize themselves and clarify their concerns. Similarly, the employees have staff councils (red) (at least) throughout the university.

In this respect, you will mainly come into contact with the student representation at university level (student parliament and the AStA, its executive) and us, the student council, at the level of the physics department. The BCGS is an additional structure maintaining the cooperation between the physics departments of Bonn and Cologne.

Elections and plenary meeting

Someone says: this is a learning process.

No one contradicts.„

Uwe Timm, Heißer Sommer

The student representatives in the committees are elected every year in December. For one week, there are ballot boxes at all ends of the university where you can vote with your student ID. (Those who are not there, e.g. abroad, can also apply for absentee voting beforehand.) Shortly before or during the election week, there are general assemblies organized by the student councils in all departments. The members of the committees of the department are elected there (instead of at the ballot box), but most importantly, it is explained what exactly is being elected and which groups are up for election, and there is a general debate about the work of the department.

How do students with employment contracts, doctoral students, etc. vote?

Especially for master and doctoral students, it is sometimes a bit difficult to understand who gets to vote for what. Basically:

- For the student representatives (yellow) and for the SHK Council, all who are enrolled have the right to vote.

- For the staff representatives (red), all those who have an employment contract with the University of Cologne (despite SHKs = students without a Ba degree) have the right to vote.

- For the collegial bodies (green), the right to vote as an employee is granted to those who have an employment contract with at least 50% of the workload at the University of Cologne. If you do not have an employment contract or have an employment contract with less hours (e.g. as an assistant), you have the right to vote as a student if you are registered.

Elections for the different member groups are held separately in time. If you are simply a student, you vote for everything once a year in December. If you also have an employment contract with 50% or more, you elect the student committees (yellow) annually in December, but the college committees (green) every two years in January and the staff council (red) every 4 years in summer.

Where do student teachers/people enrolled in multiple degree programs vote?

If there are several options for assigning someone to a department, for example, because you are studying to be a teacher or are enrolled in different programs at the same time, you have the choice of where you want to vote. In doing so, one must always decide for the entire election. If you are a candidate somewhere, the allocation is already determined by this; otherwise you can decide it when voting at the ballot box. This must be explicitly stated, otherwise you will simply be assigned to the department that is further in front in the alphabet.

(Political) university groups

As a rule, grassroots democratic lists are available for election to the student councils, university groups that can be more or less assigned to the parties are available for election to the student parliament and AStA, and alliances of all these groups are available for election to all other bodies.

In addition, there are a number of partly very active political groups at the university that do not run for the committees. They mainly work against the racism (e.g. Antifa-AK, Kölner Studis gegen Rechts) as well as for sustainability (e.g. Students for Future and EndFossil), peace (e.g. AK Zivilklausel) and human rights (e.g. amnesty Hochschulgruppe). In addition, there are groups that critically examine the (political) orientation of teaching and research in their departments (e.g. oikos, Kritische Medizinstudierende) or advocate for the interests of certain minorities (e.g. LUSK, Chinesische Hochschulgruppe). An overview of almost all groups can be found on an overview page of the university.

„Let our weapons be weapons of the mind, not tanks and bullets. What kind of a world could we build if we used the forces that war unleashes for construction.“

Einstein